It is one of the biggest rivalries in Portuguese football, and perhaps you have never heard of it. For decades, the area from the Aveiro district that connects Santa Maria da Feira, Ovar, São João da Madeira, Santa Maria de Lamas, and Oliveira de Azeméis has been fertile in tense, often violent, and undoubtedly unforgettable rivalries.

One of the fiercest is the one that opposes Feirense and Lusitânia de Lourosa, two clubs from the same council that represent very different takes on how to play the game. On Sunday 28 September they will face off in the same tier for the first time since 1984/85, but two years ago, a play-off between the clubs once again drew the spotlight in an area known as the Bermuda triangle of Portuguese football.

PortuGOAL’s resident football historian Miguel Lourenção Pereira reports.

***

It was Rosa Santos, the celebrated Portuguese referee from the 1980s who officiated in the 1988 and 1992 European Championships, who once said the worst matches he had ever had to endure were the ones that opposed Feirense, Lusitânia Lourosa, Ovarense, União de Lamas and Oliveirense. Four sides that sit in an area that stretches no more than 30 km from each other and that represent a voracious and primal sense of rivalries that goes way beyond football.

The “Bermuda Triangle” of Portuguese football

Rosa called it the “Bermuda Triangle” of Portuguese football as all sorts of values were lost in that connection of lands, souls and lost dreams. Lourosa and Feirense are both from Santa Maria da Feira, but while the Blues come from the council’s main city, Lourosa is a working-class setting that always looked with contempt on the big boys in town. In the words of the great local journalist José Bastos, for those who lived in Lourosa, it was customary to hear them say they only visited Feira, which sits less than 10 km from their home, “to pay taxes or to be arrested”. Nothing more.

That voracious mentality is what has defined the Black and Yellow over the years. They are the last Gaul village in the region, a setting where memories of the past linger, with a club run by the iron fist of the local businessman Hugo Mendes, who has invested heavily in it with a dream of turning them into a first division side like neighbouring Arouca has accomplished under the leadership of the Pinho family.

Immediate punishment

He famously, after a defeat in a local derby in São João de Ver in a cup tie, told the squad to return home on foot and sent the bus to return with no-one on board. It was only a couple of miles, but the message said it all. Win at all costs or pay the price. Lourosa have never played first division football, and yet the die-hard love for the club in town is one of a kind. Even when they were playing in the fourth and third tier, the club regularly drew attendances of more than 5,000 spectators, more than many first division sides, let alone sides from the second tier.

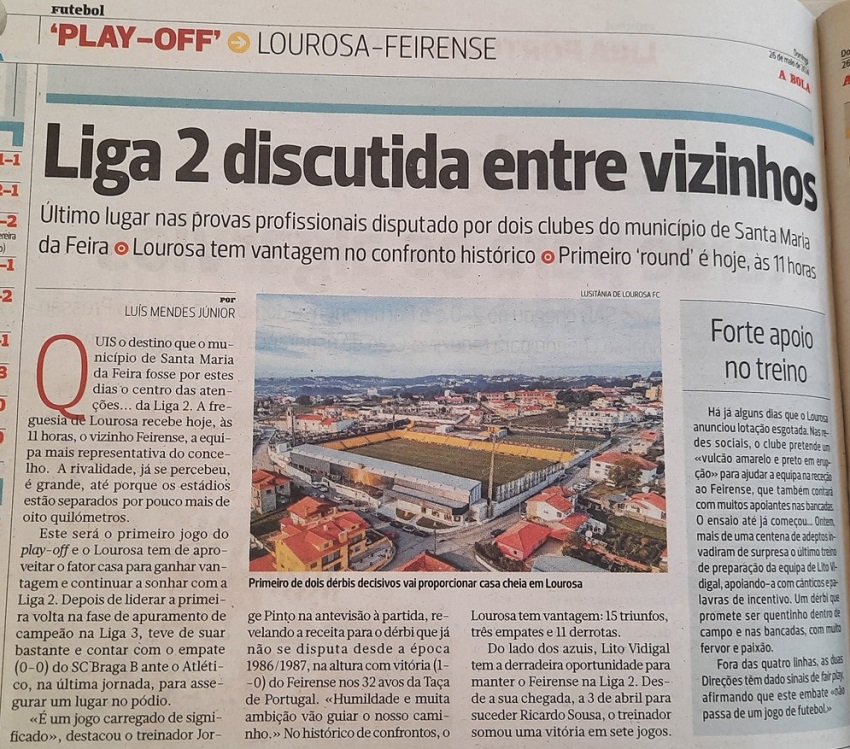

They are likely the best followed club in the Aveiro district, an area where there are not many clubs with long spells in the first division (Beira-Mar remains the symbol of the region) but whose faithful supporters always manage to guarantee a vibrant atmosphere in home matches, particularly when clubs face bordering towns. And there was such a crowd when the two biggest sides of the Feira council met for the play-off that would decide who would play in the second tier in 2024/25.

“Anyone but them!”

Feirense had had a poor season, and for a while, supporters were already prepared for the worst. In the final months of the Liga II campaign, their greatest fear wasn’t just to be relegated but to do so at the expense of Lourosa, who were fighting for promotion from Liga 3. In the end, the most dreaded outcome unfolded. Lourosa failed to grab one of the two automatic promotion places, while Feirense avoided automatic relegation but were forced to face their rivals in a play-off that was much more than just about football.

The last time they had played against each other was back in 1984/85, when they were both in the second-tier northern section (at a time when the second division was divided into three geographical areas). They both ended with 27 points in the table, with Feirense gaining the upper hand thanks to the favourable head-to-head results. After those encounters, the two clubs suffered different fates. The sides were separated administratively the following season, with Feirense playing in the centre division and Lourosa remaining in the north section.

Lusitânia were relegated to the third tier in 1988, while Feirense were promoted to the first division the following season. They had never met since then, so expectations couldn’t have been higher going into the two-legged play-off.

Welcome to hell

The first match was due to be played in Lourosa and was sold out instantly. The locals had a decent and ambitious project that vigorously aimed to be among the professional leagues, and Feirense’s dynamics were poor at best. The eight kilometres that separate both grounds turned out to be a via crucis for the Fogaceiros, who had all the pressure to perform. They knew hell was waiting for them once the Lusitânia ground appeared on the horizon, and they got the welcome everyone expected. It was going to be an old-fashioned derby; the kind of match Portugal football had forgotten existed by turning its back on its regional and local divisions. Even the football league was aware of what was about to happen, appointing the international referee Artur Soares Dias to officiate the match.

The locals, coached by Jorge Pinto, soon took control of the match as everyone imagined they would. In the first ten minutes they won four corners and two free-kicks, permanently harassing the Blues’ defence, who knew they were in for a hard time. In the 17th minute, the locals opened the scoring with the ball entering João Costa’s net after a rumble in the box, but it was eventually disallowed. The now FC Porto goalkeeper saved his side time and time again as both teams stayed in position, Lusitania having much more of the ball and creating danger at ease, and Lito Vidigal’s men suffering stoically and waiting for a chance to counter.

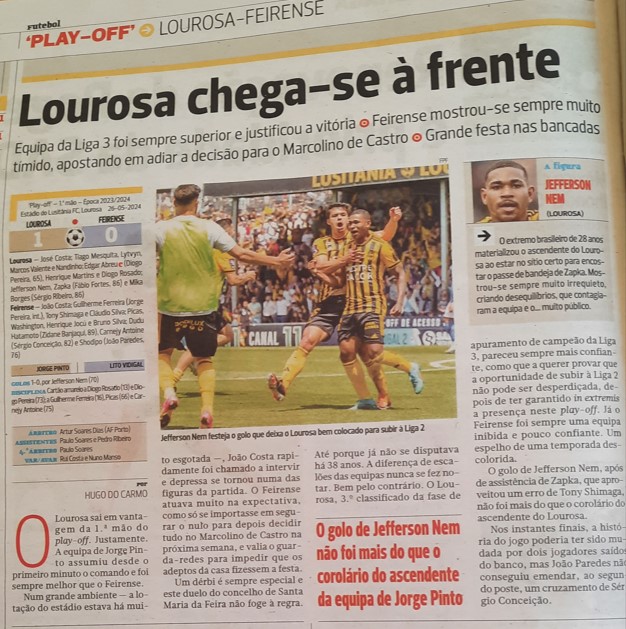

Costa’s goal finally breached

The first time Feirense caused any harm to the locals’ defensive line happened on the brink of the hour, but Antoine’s shot was feeble with José Costa saving easily. Once again, the run of play turned in Lusitânia’s favour as the side kept pressing to find an opener. In the 70th minute they finally got a much-deserved reward when a cross by Zapka took everyone from Feirense by surprise. A few fumbles later, but ball luckily found its way to Jefferson Nem at the far post, and the Brazilian striker only needed to tap it in the net. The crowd went wild after more than an hour of nervous suffering while the Feirense players looked at each other, knowing they had it coming.

But if you thought they would set themselves for a fightback, you would be mistaken. It was Lourosa who fiercely pressed for a second goal while Vidigal desperately shouted at his men to hold on for the rest of the match, figuring that a one-goal deficit wouldn’t be enough to deter them from reaching their goal in a week’s time in the home leg. And so the match ended with the locals once more causing mayhem on João Costa’s box, but with the goalkeeper performing to expectations to salvage the day time and time again.

In the end, while the supporters celebrated enthusiastically, Jorge Pinto seemed worried. He knew that Lourosa’s home advantage was one of their biggest weapons, especially in such a demanding emotional derby, and they had squandered a golden opportunity to score more than just the single goal. He was proved right, sadly for Lusitânia.

Feirense too strong at home

Days later, at the Marcolino Castro, probably one of the most underrated pitches in Portugal, Feirense came out on top. Now spurred on by their own fanatical fanbase, the Fogaçeiros came out victors, netting three past José Costa, with Sérgio Conceição, the son of the then Porto manager of the same name, netting a brace, and Henrique Martins scoring an own-goal in the dying minutes of the tie.

By then, as the away side searched madly for a goal that would level the tie on aggregate, that own goal triggered an eruption in celebrations not only at Santa Maria da Feira, but even in the neighbouring county of Lamas, who joined Feirense’s party simply to enjoy their local rival’s demise. Feirense won the right to play another season in Liga 2, where they once again struggled to stay up, although this time they did so without the need of a last-minute playoff.

Lourosa on the up, Feirense standing still

Lourosa learned from their mistakes and have invested further in infrastructures as they remained focused on getting promoted, which they eventually did by topping their Liga 3 section, thus avoiding unnecessary drama. It is now the first time in four decades that the sides will be playing against each other in the second tier, and expectations are high as Oliveirense, also a local rival from Oliveira de Azeméis, is also one of the 18 clubs in Portugal’s second tier striving to get into the top flight.

With historical clubs such as Sporting de Espinho, Beira-Mar and Ovarense down in the lower leagues, as well as Sanjoanense and União de Lamas, the Portuguese Bermuda Triangle is alive and well in the professional football leagues once more. Expect tension, drama, fanatical local supporters and old scores to settle. Everything Portuguese football usually lacks. As Bette Davis’ character in All About Eve says, “it’s going to be a bumpy ride.”

By Miguel Lourenço Pereira, author of “Bring Me That Horizon – A Journey to the Soul of Portuguese Football”.